How to create a civilization

Let's say we want to seed a civilization of cultural aliens on another planet. The only rule is that we can't give them any of our own cultural products - no technology or know-how. They start from the proverbial state of nature, just like we had to. How would we do it? Is there any law or guiding principle that we can glean from the way societies evolved on our own planet?

From the outset, we should define what we mean by civilization, without getting bogged down in semantics. We all know a civilization when we see one. Multiple social classes, a large bureaucratic system of governance, urban living, economic specialization, writing and a vast geographical range - these are some of the hallmarks of civilization.

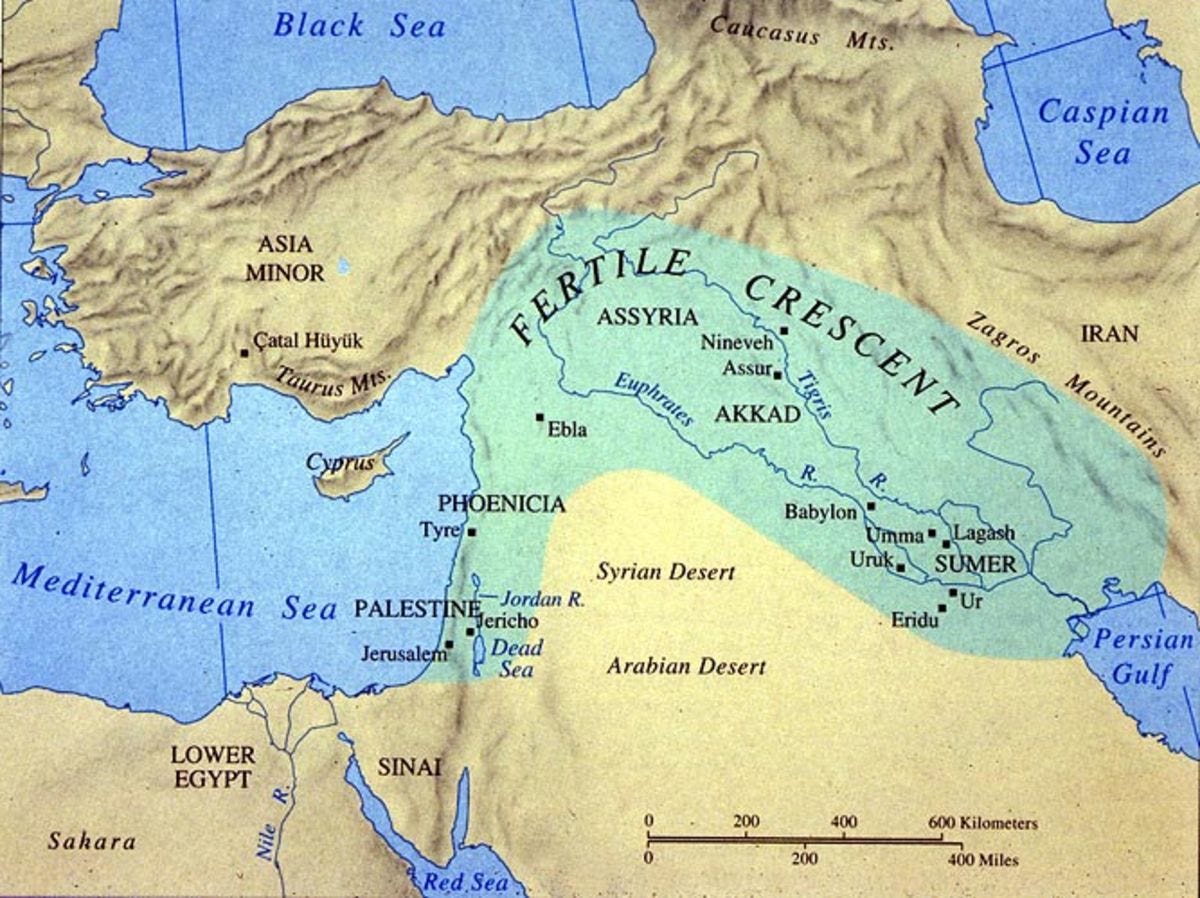

Clearly, civilizations do not emerge out of nowhere. Before the Sumerian civilization blossomed in what is today the Middle East, there were thousands of years of agrarian farmers and herders. Before the modern West, there was the scientific revolution. Before the scientific revolution, there was the Gutenberg printing press. Before the Gutenberg printing press, there was the invention of paper, ink, and a literate population. We can dimly sense that there must be a relationship between these things, yet how could we possibly isolate them fully?

Efforts to untangle these causal links is akin to tracing the lineage of a forest in terms of every plant that had to decompose in it’s soils, every bird that distributed it’s seeds, and every rodent that defecated on its roots. Even if we understood all pieces in play, setting them up like dominos to fall would be impossible since the existence of later pieces is dependent on earlier ones. Our job is to set the initial parameters; the base environmental conditions that are suitable to grow a civilization. Just as a rainforest will emerge, given enough time, in an area with a suitable climate, what is the climate in which our civilization can take root?

To answer this question, we need to think of civilization more broadly. A civilization is nothing but a particular kind of human culture. Not all humans live in civilizations, even in the modern world. For most of our species’ history, we lived as roaming bands of hunter-gatherers. Every civilization that has ever existed can, in theory, trace its emergence to our foraging prehistory. Genetically speaking, we are the same animal we were 200,000 years ago. Our bodies and minds haven’t evolved, but our culture, at certain times and places, has. Remembering that our alien population are cultural creatures like ourselves means that nudging them in the direction of civilization is the same thing as promoting the evolution of their culture.

What though, do we mean by culture? Naturally, rigid definitions are impossible. Perhaps the most useful way for our purposes is to define culture in terms of its function.

All organisms, as put by Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene, are survival machines built by genes to carry themselves through time. One has the image of a blob of primordial muck at the controls of a hulking automaton. The image gives the impression of sentience on behalf of the genes, but that is far from the truth. Genes don't behave a certain way as much as they tend towards certain behaviour, just as a ball released at the top of a hill will tend to roll downward.

Every generation, a consortium of genes program their host from scratch. If they do a good job, that host will live to create copies of itself, all of them housing more or less the same consortium of genes, minus a few lost to corruption, plus a few new ones gained by merging with other genes. A useful, if imperfect, analogy is to think of genes like a virus, jumping from host to host across the generations. The better their hosts perform out in the world, the more they replicate, and the greater the proportion of their genes exist compared to rivals. The important point for us is that human beings are, like every other organism, merely a vehicle for genes to propagate themselves into the future.

What then, of culture? If humans are a vehicle for genes, then culture is a vehicle for humans. Humans function to propagate specific genes, and culture functions to propagate specific humans. Seen this way, we might say that culture is a symbolic, or conceptual system whose job is to serve human needs. The needs of humans are like that of all animals, to secure food and reproduce. Culture helps us to do so by encoding and distributing information for how to obtain and process food, but also to show respect, demonstrate loyalty; it provides the rituals and norms for upholding social cohesion.

I said earlier that we should be aiming to promote the evolution of our alien's culture. Such terminology understandably raises eyebrows. Am I saying that some cultures are more evolved than others? Actually, yes. I take evolution to be analogous with complexity. In other words, the more evolved something is, the more complex it is. This is consistent with the original meaning of the word evolve - to unfold, open out, expand.

In other words, to add to oneself. Complexity, from the Latin root com - together, and plectere - to weave, also gives this impression, that of multiple disparate parts coming together to form a cohesive whole.

Therefore, if culture is a system made of different units of information, then its complexity is a measure of both the amount of cultural information and the number of relationships between those bits of information. The fewer those unique relationships, the simpler the system.

It's important to note that we are talking here not about the internal, psychological lives of the individuals themselves, but their culture; that is, their artefacts, symbols, mythologies. An hour spent on YouTube can expose someone to vastly more cultural information than an hour spent with an Inuit hunter-gatherer, but that says nothing about the ingenuity of the Inuit nor the richness of his daily experience.

With that preamble out of the way, how on earth do we explain why some cultures became more complex than others? If we can find an answer to that, then perhaps we can isolate the key principles driving their disproportionate growth.

We must recognize that culture has no power whatsoever until expressed in human behaviour. It is not some gaseous cloud mysteriously governing human affairs. It manifests itself in discrete, physical acts - throwing a spear, threading a needle, whistling a tune. Culture is a material phenomenon. As such, it is beholden to the laws of physics to which humans and every other organism is bound.

Can physics really explain something as malleable as culture? The 20th century anthropologist Leslie White thought so. He argued that culture, like all life, is a thermodynamic system. It takes in energy from its environment and spits it out the other end in degraded form. Every organism can be seen, as White put it, as a "structure through which energy flows''. Energy is taken in as sunlight or nutrients, put to work in the growing of leaves or the lifting of feet, and expended in the form of heat.

Why should culture be any different? When there are abundant energy sources, foods to be harvested, soils to be planted in, rare metals to be traded, then the potential for culture to evolve is great. This basic relationship was put by White the following way:

“culture develops as (1) the amount of energy harnessed and put to work per capita per unit of time increases, and (2) as the efficiency of the means with which this energy is expended increases"

What jumps out here is that the capacity for culture to evolve is not solely dependent on the energy harnessed, but also on the efficiency with which it can be harnessed. Since the work we can do with our physical bodies is constant--the same, if not less, for a modern Western man as an Inuit hunter--White simplified his law to:

“Other things being equal, culture evolves as the productivity of human labor increases”

Technology was for White a crucial ingredient. He formalized the law as:

E x T = P

in which E represents the energy input, T the technological means of utilizing it, and P, the cultural product that results.

What does this formula predict? It predicts that hunter-gatherer societies with simple technology, living in environments that cannot support large populations, will tend to remain small. This is what we see across the historical record, with the Netsilik Inuits of the Arctic and the !Kung of the Kalahari desert as prime examples. The cultures of these groups are perfectly aligned with their ecological reality. Scarce resources make infanticide an acceptable strategy for dampening population growth. Because everybody knows each other, there is no need for large governance structures or distinguished leaders - communal decision-making comes naturally.

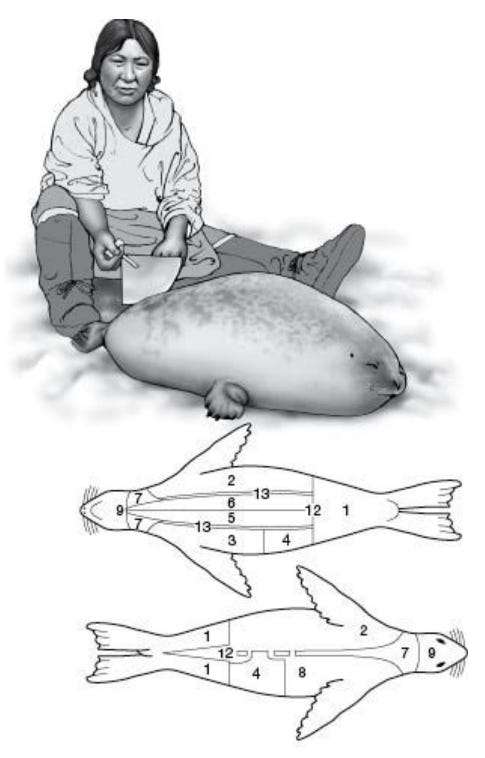

Even the perils of subsistence living are counterbalanced with mutual-aid networks. Netsilik boys, for example, are assigned 12 male partners when they come of age, with whom they share the meat of their seal hunts. This partnership of allies gives the boy and his family a social security blanket, a network of allies whose door they can knock on in times of need. What all these cultural norms do is relate the individual to his specific environment in such a way as to best sustain the group.

White's law also predicts that if circumstances change, if say a society with a certain level of cultural complexity moves into an environment with less resources, then it's culture will lose complexity. We can see this phenomenon at work with the Moriori people of New Zealand's Chatham Islands. After moving from the fertile soils of subtropical New Zealand to the harsh subantarctic Chatham islands, 800km out to sea, they proceeded to shed many of their cultural traits. The Chathams were not suitable for agriculture, and so, despite being descended from farmers, the Moriori devolved into a culture of hunter-gatherers, subsisting on seals, shellfish, seabirds and fish. By the time they had contact with outsiders again hundreds of years later, they were a small population that had renounced violence, without strong leadership or organization. This would unfortunately be the undoing of their way of life, as they were decimated by displaced Maori from New Zealand looking for a new home. In contrast, the land the Moriori originally left was packed with Maori tribes producing reliable food surpluses. Not all Maori had to devote their time to procuring food, and so could work as part time soldiers, craftspeople, fort-builders, and tool-makers, fueling consequent development in military strategy, technology, and art.

The most dramatic growth in culture however seems to follow in the wake of technological innovations that unlock new sources of energy. Take the Chumash Indians of California. For 5000 years, they subsisted on acorns and seafood as an egalitarian society of hunter-gatherers. Large fish were a problem though - the Chumash had simple canoes made of bulrushes that made hauling large game problematic. A critical technological innovation allowed them to transcend this limitation: the tomol canoe. Made of redwood or pine, these could be up to 7 meters long and hold 12 people. Crucially, they could make longer journeys out to sea, allowing them to haul in massive swordfish and tuna. They could also now efficiently move between the mainland and the Channel Islands off the coast, a rich source of flint which they used to carve beads from seashells. These beads were valued by inland groups and even became a regional currency. As producers and middlemen for the shell trade, the Chamush were able to profit handsomely. As their population grew it developed a hierarchy, with chiefs administering over the production of tomals and seashell beads. Some the labourers even came from outside the Chumash kinship group, forming a multicultural society collectively benefiting off the local industry.

What these specific cases illustrate is a general principle: that the more energy input that goes into a cultural system, the more complex that system will tend to become. A simplification of the general evolutionary logic, which admittingly misses the endless historical permutations and exceptions, goes something like this:

More resources are able to feed more mouths, more mouths means more hands, and more hands means even more resources.

This autocatalytic process extends to technological innovation. Every individual might have a small chance at discovering some new way to string a bow, but the more individuals trying, the more likely that one of them will, and once they do, the whole group will benefit. Every innovation helps the group to procure more resources with less effort, further accelerating population growth.

A growing population necessitates a growing body of rules. The group has to make decisions and mediate conflict. Often the way to do this is to put someone in charge - a chief. As groups grow, competition for leadership splits groups into disparate parts, each following their own leader. The most successful groups are those able to incorporate the subgroups into larger groupings, creating hierarchies of governance. When more than one of these groups are competing for shared resources, conflict will be won by those with superior social cohesion, allowing them to fight more effectively and develop trading networks with other societies.

Time and again throughout history we see civilizations rise in this way through the domestication of plants and animals, a hitherto unmatched energy source. The yield obtained by harvesting directly from the chance offerings of nature simply cannot be matched by the intentional cultivation of resources.

The reasons why agriculture kicked off initially in some places and not others comes down, again, to the energy sources available. The Sumerians flourished due to the ease of domesticating high yield cereal and pulse crops, as well as sheep and goat, all of which had evolved in the favourable climate and geography of the Eastern Mediterranean. Similar stories can be told in China, Central America, and the Andes.

The civilizations that rose in these areas hit their natural limits when they exhausted the resource base, which is why we never saw Romans launching rockets into space. The ceiling for our own civilization is clearly much higher, the result of an even higher yield energy source: fossil fuels. The bewildering complexity of our own culture--all our occupations, technology, and art--all springs, ultimately, from coal, oil, and natural gas. Augmenting human labour with them has led to the highest levels of productivity and cultural complexity in history.

Yet our large-scale exploitation of fossil fuels did not happen in a vacuum. Humans have used them for thousands of years. The Romans used to heat their public baths with it. Over two thousand years ago the Chinese were extracting natural gas and oil from wells. Yet it’s only very recently that we used it to power our home, vehicles, and factories. If we’ve had the energy source around for so long but neglected to build a civilization with it, couldn’t our aliens fall into the same stasis?

It’s entirely possible that they could. But then, given enough time, they would be likely to figure out how to exploit it fully. Your odds of winning the lotto aren’t bad if you buy a ticket every week for a hundred million years. The mix of social, economic, and technological prerequisites that were needed for the industrial revolution to take place I’m nowhere near qualified to survey, but it seems reasonable that they would have emerged at some point. Just as a river might take thousands of years to carve a channel to the ocean, so does cultural evolution proceed to pinch and probe the environment in order to discover some better way of doing things. Whether or not the configuration it finds represents the final peak before regression, or merely another step in the insatiable march toward complexity, is beside the point. Culture never stands still, and that’s where it’s tendency for growth comes from.

The prescription for our alien experiment therefore is clear - put them somewhere with a high energy source, and wait. White’s law tells us that cultural evolution will ride on the back of human productivity. For that to happen, latent energy sources must be tapped. Our aliens may take thousands of years to figure out how to make use of them. They may get the ball rolling only to degenerate into social anarchy multiple times over. Eventually though, their probing roots will stumble upon fertile ground, and they will find it a strong foundation for their civilization. At least, for a while.